Camp Perry, the Bataan Death March, and Port Clinton’s M1 Carbine Legacy

As a Port Clinton visitor and service rifle enthusiast, I never expected a routine grocery run to Bassett’s Market to lead me into World War II history. Yet behind my favorite market – Bassett’s, known for its hometown charm – loom the remnants of an abandoned factory with an incredible story. That crumbling plant near the shores of Lake Erie once helped arm U.S. troops, and its fate is entwined with both Camp Perry and the infamous Bataan Death March. Welcome to the Garand Thumb Blog’s deep dive into Port Clinton’s forgotten WWII legacy (delivered in true Garand Thumb style).

The Abandoned Factory Behind Bassett’s Market

The long-abandoned Standard Products factory behind Bassett’s Market in Port Clinton, photographed shortly before its demolition. During WWII, this plant produced M1 Carbines for the U.S. military, but it sat empty for decades afterward as a rusting, barbed-wire-encircled ruin.

If you’ve driven past Bassett’s Market on East Perry Street, you might recall glancing at a cluster of silent, rusted buildings behind it. For years, I barely gave that old complex a thought beyond noting how eerie it looked. In reality, that Maple Street factory was once Standard Products Company’s Port Clinton Division, which thrived during the 1940s. At its peak in the 1950s the plant provided nearly 1,000 good-paying jobs, anchoring the town’s prosperity. Fast-forward to the 1990s: after decades of layoffs and decline, the plant’s gates finally closed in 1993, leaving behind a fenced-off shell marked with EPA warning signs about contamination. The photos I snapped show the grim aftermath – crumbling walls, broken windows, and coils of razor wire guarding nothing. It’s hard to imagine now, but this ghostly site was once humming with war production.

Standard Products and the M1 Carbine in WWII

Behind Bassett’s: Camp Perry, the Bataan Death March, and Port Clinton’s M1 Carbine Legacy

As a Port Clinton visitor and service rifle enthusiast, I never expected a routine grocery run to Bassett’s Market to lead me into World War II history. Yet behind my favorite market – Bassett’s, known for its hometown charm – loom the remnants of an abandoned factory with an incredible story. That crumbling plant near the shores of Lake Erie once helped arm U.S. troops, and its fate is entwined with both Camp Perry and the infamous Bataan Death March. Welcome to the Garand Thumb Blog’s deep dive into Port Clinton’s forgotten WWII legacy (delivered in true Garand Thumb style).

The Abandoned Factory Behind Bassett’s Market

The long-abandoned Standard Products factory behind Bassett’s Market in Port Clinton, photographed shortly before its demolition. During WWII, this plant produced M1 Carbines for the U.S. military, but it sat empty for decades afterward as a rusting, barbed-wire-encircled ruin.

If you’ve driven past Bassett’s Market on East Perry Street, you might recall glancing at a cluster of silent, rusted buildings behind it. For years, I barely gave that old complex a thought beyond noting how eerie it looked. In reality, that Maple Street factory was once Standard Products Company’s Port Clinton Division, which thrived during the 1940s. At its peak in the 1950s the plant provided nearly 1,000 good-paying jobs, anchoring the town’s prosperity. Fast-forward to the 1990s: after decades of layoffs and decline, the plant’s gates finally closed in 1993, leaving behind a fenced-off shell marked with EPA warning signs about contamination. The photos I snapped show the grim aftermath – crumbling walls, broken windows, and coils of razor wire guarding nothing. It’s hard to imagine now, but this ghostly site was once humming with war production.

Standard Products and the M1 Carbine in WWII

During World War II, Port Clinton’s Standard Products factory switched from making auto parts to making guns. In 1942 the U.S. government contracted Standard Products to produce the new M1 Carbine, a lightweight semi-automatic rifle designed for support troops. Over the next two years, this local plant turned out approximately 247,160 M1 Carbines – about 4% of all M1 Carbines made during the war. (For context, the M1 Carbine was a smaller cousin to the famed M1 Garand rifle – and unlike the Garand, it wouldn’t give you a “Garand Thumb” when loading it, since it used a detachable magazine instead of an en-bloc clip!) The Port Clinton workers became quite proficient: each carbine cost the government only about $53.79 to produce, a worthwhile investment considering the firepower it gave our troops.

Standard Products Co. was actually an auto parts manufacturer founded by an inventive physician, Dr. James S. Reid, around 1930. They made things like window channels and gas caps for cars. The war effort was a massive pivot – suddenly this small-town factory had to mass-produce a .30-caliber rifle that soldiers would carry into battle. They succeeded, even though they didn’t end up using all the serial numbers allotted to them (they stopped production in 1944). After WWII, Standard Products even got government contracts to refurbish and upgrade M1 Carbines for long-term storage – adding features like bayonet lugs and better sights to many of the very guns they had originally built.

So who were the people building these rifles? Port Clinton in the early 1940s didn’t have a huge labor pool, and many able-bodied men were off to war. Here’s where the story takes a poignant turn connecting to Bataan: the ranks of Standard Products’ workforce were filled by the women and older family members of local soldiers. In fact, many of those who answered the call for workers were wives, parents, grandparents and siblings of Port Clinton men who had been lost in the Philippines. Early in the war, a local National Guard tank unit (Company C of the 192nd Tank Battalion) had been deployed to the Philippines – and met a tragic fate at Bataan (more on that shortly). When Standard Products announced it needed employees to meet wartime production, the community responded. Even people who already had day jobs took on evening shifts at the plant, determined to do their part. Many of them had a deeply personal motivation: they were producing weapons for the Army at the very same time their sons or husbands were POWs of the Japanese. It’s incredible to think about Port Clinton’s home-front contribution – literally fueling the fight with rifles made by those enduring their own sacrifices back home.

To put the M1 Carbine in perspective, here are a few key facts about Standard Products’ role in its production:

- Total Carbines Made: ~247,160 carbines (Standard Products accounted for roughly 4% of overall M1 Carbine production in WWII).

- Manufacturer’s Code: Carbines and parts from this plant were stamped with an “S” or “STD.PROD.” marking, identifying their Port Clinton origin. Collectors prize these for their relative rarity (Standard Products made the third-fewest carbines of all contractors).

- Cost and Efficiency: $53.79 average cost per rifle to Uncle Sam. The company was efficient enough that it never even used about half of the serial numbers it was allotted before the war ended.

- Post-War Work: After 1945, Standard Products was tasked with retrofitting carbines for future service (adding bayonet lugs and adjustable sights) – a testament to the quality of the rifles it had built. Many WWII-era carbines were thus updated in Port Clinton before being placed in arsenals or sent overseas again during the Korean War.

In short, the old factory behind Bassett’s Market was a crucial node in America’s WWII supply chain. The next time you pick up groceries or stop for hardware in that part of town, remember that an army of local moms and dads once punched the clock right there, turning out rifles to help win a war.

Camp Perry and the Bataan Death March Connection

Just west of Port Clinton lies Camp Perry, the Ohio National Guard training base famous for its rifle ranges and National Matches. Camp Perry is where our local tank unit, Company C, 192nd Tank Battalion, was based before shipping out. In November 1940, 42 men from Port Clinton’s Company C said goodbye to their families and left Camp Perry for further training at Fort Knox. They eventually found themselves on the other side of the world, battling the Japanese invasion of the Philippines. On April 9, 1942, Bataan fell. Company C’s Ohio boys became part of the Bataan Death March – the brutal forced march of American and Filipino POWs in tropical heat with no food or water. Of the 32 Port Clinton men from Company C who were on Bataan at the surrender, only a handful survived the ensuing Death March and the 3½ years of captivity that followed. Most perished from starvation, disease, or abuse in POW camps. The impact on our small community was devastating – almost everyone in town knew someone who was lost.

Today at Camp Perry, their sacrifice is not forgotten. In 1984 the Ohio National Guard dedicated the Bataan Armory on base in honor of Company C’s heroes. Outside the armory, a somber plaque shaped like Ohio lists the names of the Port Clinton men and tells their story. A World War II M3 Stuart light tank, the same type they fought in, stands vigil nearby – a gift from citizens of Dunkirk, Ohio, accepted on behalf of Company C as a memorial. Camp Perry’s memorial plaza ensures that each visitor hears about the local tank company that went through hell in Bataan.

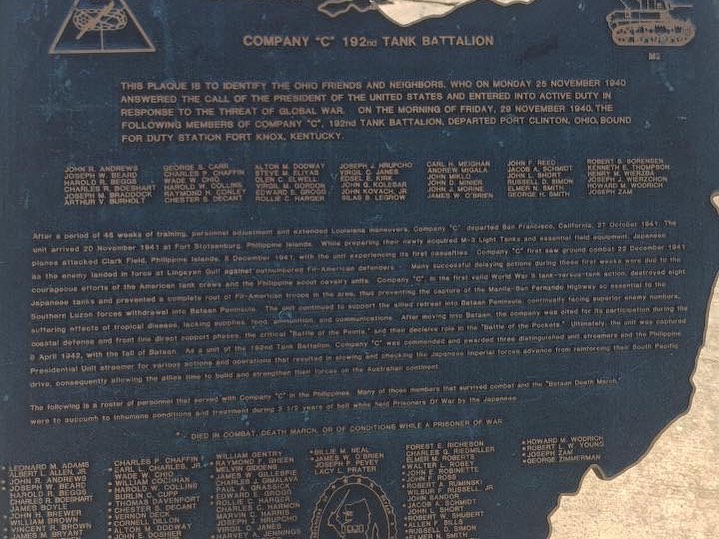

A memorial plaque at Camp Perry’s “Bataan Armory” honors the men of Company C, 192nd Tank Battalion from Port Clinton. Forty-two neighbors and friends deployed, and after the fall of Bataan only “a few survived the Bataan Death March” and years as POWs. The armory was officially named for their unit in 1984.

The connection between the Bataan Death March and the Standard Products factory makes Port Clinton’s WWII story uniquely poignant. While Company C’s soldiers were enduring one of the war’s greatest tragedies overseas, their families were contributing to victory on the home front by building the very weapons needed to bring those soldiers (and thousands of others) home. In fact, an historical account notes that many who went to work at Standard Products did so because they had lost loved ones at Bataan, and they were determined to help the war effort. It’s a powerful example of a community turning its grief into action. Every M1 Carbine that rolled off the Port Clinton assembly line was more than just a rifle – it was a symbol of resilience and revenge, a small hometown’s answer to the sufferings of its sons in combat.

Honoring a Legacy of Service

From the quiet shores of Camp Perry to the empty lot behind Bassett’s, Port Clinton is filled with reminders of its wartime legacy. What was once a bustling factory is now gone – “demoed” and cleared, with only memories and a few photos like mine to mark its existence. But the stories forged there remain alive. The next time you find yourself in Port Clinton, pause for a moment. Whether you’re browsing Bassett’s Market (I personally never leave without one of their fresh donuts and a smile from the staff) or attending the National Matches at Camp Perry, you’re walking in the footsteps of ordinary Americans who achieved extraordinary things. They endured the unendurable, from garand-thumb bruises during rifle practice to heart-wrenching losses on the battlefield. And through it all, they kept marching – or working – forward.

Here at Garand Thumb Blog, we aim to keep these memories alive for future generations of shooters and history buffs. Port Clinton’s WWII legacy shows how a small town made a big impact. It’s a legacy of service and sacrifice we should never forget, and one that gives our community a lasting place in the chronicles of World War II. In the end, the story behind Bassett’s is about more than an old building – it’s about the people whose grit and determination continue to inspire, long after the rifles have fallen silent.

Sources: Historical data on Standard Products’ M1 Carbine production; Camp Perry and Company C memorial information; first-hand local accounts of Bataan and war production efforts; and recollections compiled in Pacific Standard’s Rust Belt feature.